The Most Confusing Lord Of The Rings Moments Explained

Peter Jackson's trio of Lord of the Rings movies will forever be the definitive Middle-earth adaptation. There are simply too many things to love. With its ambitious scope and expert casting, attention to detail and staggering run time, all coupled with a breathtaking score, there are so many reasons that this is the one trilogy to rule them all.

And yet, "the best" is a far cry from "perfect." Many points in the movies cause viewers to pause. There are spots where the story takes an odd turn or jumps between scenes with little to no explanation. It can even get confusing if you're a fan of the books trying to reconcile the source material with changes made for the silver screen version. Things like internal dialogue and detailed exposition don't always translate easily to a visual format.

It doesn't matter if you're a fair-weather friend of the films or a diehard fan of the original books, there are points in the Lord of the Rings movies that are downright confusing. We've rounded up the biggest head-scratchers of them all and done our best to explain (and when possible, resolve) these inconsistencies. So, let's take a deep dive into Middle-earth lore in order to address some of the baffling bewilderments and try to bring Jackson's masterpiece a bit more into focus.

Gandalf, a Balrog ... and teleportation?

The Two Towers opens up with a scene in which the fate of the supposedly deceased Gandalf is shown. Last we'd seen the wizard, he and the Balrog had tumbled into the abyss spanned by the Bridge of Khazad-dûm. Not one to go down easy, Gandalf is shown retrieving his sword mid-fall and then tussling with his fiery foe as they hurtle into the lowest depths of the mountains. Eventually, they crash into a dark, cold lake in the belly of a subterranean cave. Later on, when Gandalf explains what happened, the combatants are suddenly shown dueling on the highest peak of the mountain, which ...what? The only explanation we're given to work with is Gandalf's vague account that they fought "from the lowest dungeon to the highest peak."

Okay ... but how do they suddenly teleport from the lowest to the highest point in a mountain range? Let's turn to the books for some clarification, shall we? In The Two Towers, Gandalf helpfully details that the pair fought their way through dark tunnels that had been "gnawed by nameless things" that were even older than Sauron himself. In this way, the pair reach a legendary dwarven staircase called the "Endless Stair." These ascend "in unbroken spiral in many thousand steps" until they reach the pinnacle of the mountain above. So, while it may not make for flashy cinema, it turns out that a big part of Gandalf's epic duel with the Balrog was little more than a long-distance race up a staircase. Nice.

What's up with Arwen's impeccable timing?

After he's shown the true nature of the One Ring, Frodo and his friends leave the Shire in an attempt to get the overpowered bauble to Rivendell. They hook up with Aragorn in Bree, which is a major plus, but their journey is seriously complicated after one of the Dark Riders stabs Frodo with a poisoned blade on Weathertop. The group of friends nearly despairs until — hey, presto! — Arwen shows up out of nowhere to save the day.

The daughter of Elrond says that she's been looking for them for two days, and in the heat of the moment, it's easy to excuse her arrival as little more than good fortune. But when you stop and think about it, how did she know where they were ...or why they were traveling ...or when they would even be in the area?

It turns out that Arwen actually has nothing to do with this part of the story in the original book. In The Fellowship of the Ring, the travelers are saved by an ancient elven hero named Glorfindel who's operating as part of a larger rescue mission. This operation is set in motion when Elrond receives word of Frodo's journey via a group of elves who ran into the hobbits while they were leaving the Shire. While it did give Liv Tyler's character more screen time, shoehorning Arwen into the place of an entire rescue mission didn't do much to keep things comprehensible.

What 'two towers' are we talking about?

Middle-earth has plenty of tall structures, so calling one of the installments The Two Towers makes a lot of sense. When you pause to consider the title, though, it's difficult to pick out which "two towers" are being discussed. After all, there's Saruman's tower of Orthanc, Barad-dûr in Mordor, the Ringwraith's tower at Minas Morgul, Minas Tirith in Gondor, and Cirith Ungol near Shelob's lair. Which pair is being referenced in the title? It turns out, Tolkien didn't even know at first.

The Two Towers is a very divergent story that traces the various members of the Fellowship of the Ring as they scatter across Middle-earth. This makes it a difficult story to definitively title. In multiple letters to his publisher, the author wrestled with the connotation and confusion that comes from narrowing things down to two skyscrapers without specifying which ones they are.

Eventually, though, Tolkien appears to have finally made up his mind and committed to a pair of structures that certainly define the directions that the two halves of the book go in. He himself drew a book cover for the novel that officially showed Orthanc and Minal Morgul as the two towers in question, indirectly bringing the issue to a conclusion.

What's up with the eagles?

One of the most common questions floated out there is why the eagles weren't used to make a quick flight to Mordor where they could deposit the One Ring right into Mount Doom by airmail. While this makes sense on the surface, it's actually pretty easy to debunk if you take the time to break it down.

First off, the eagles aren't pets, nor are they necessarily your typical "good guys." In The Hobbit, Tolkien says that, "Eagles are not kindly birds. Some are cowardly and cruel." He does go on to clarify that the particular eagles we meet in his stories are "proud and strong and noble-hearted." Nevertheless, they're distinctly disconnected from and disinterested in the affairs of creatures that walk the earth.

Even so, they do show up at the end of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Where do they come from? Why do they arrive just in the nick of time? This is partly because, while disinterested, at times the eagles of Middle-earth serve a higher spiritual function as messengers of the angelic guardians known as the Valar. This leads them to get involved in the action at specific moments. Additionally, Tolkien purposefully used dramatic entrances and last-minute heroics as a way to drive home the high points of fantasy storytelling. It's something he referred to as a "eucatastrophe," and one of his best eucatastrophic tools was the high-flying eagles.

Is Theóden literally possessed by Saruman?

Saruman is a powerful wizard, but can he really control individuals a hundred miles away as if they're dancing on a string? That's what we see in the movies, anyway. In The Two Towers, when Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli arrive at the Golden Hall, they find that they're anything but welcome. Gríma Wormtongue has the king well in hand and is fiendishly directing government policy from behind the throne.

However, when Gandalf confronts King Théoden — while his three companions violently restrain the king's guards, no less — it turns out that it's Saruman himself who's kicked out of the old man's brain. Literally, the scene ends with Saruman talking through Théoden and then being physically thrown back from his seeing stone in Isengard. Théoden's face then transforms back to its original form right there on the spot.

The entire sequence feels a bit forced, and it turns out yet again that it's nothing like the original. The guards don't literally get into a fistfight with the travelers, and the primary opponent is Wormtongue, not Saruman. Strong phrases are certainly used, like, "You have sat in the shadows and trusted to twisted tales and crooked promptings," and, "[Théoden] drew himself up, slowly, as a man that is stiff from long bending over some dull toil." But it never states that he's literally freed from Saruman's possessing spirit. Perhaps this one can simply be attributed to some horror-themed theatrics on the part of Peter Jackson.

Are orcs cannibals?

In The Two Towers, Pippin and Merry are orc-dragged across Rohan at terrific speed. Toward the end of the uncomfortable adventure, the orcs and Uruk-hai become fed up with their diet of maggoty bread. One of them suggests devouring the two hobbits as a delectable entrée. This leads to one of the villains being decapitated, and with meat back on the menu, the entire company eats their deceased companion right there on the spot.

The scene is unsettling, to say the least. While orcs are nasty creatures, the fact that they would not only kill but casually consume one of their own is something that turns off most sentient creatures. Once again, it turns out it's an activity that doesn't line up with Tolkien's original story, either.

On the contrary, in the books, we hear about orcs wanting to eat horseflesh. The Uruk-hai also love Saruman because he "gives us man's-flesh to eat." However, the concept of delightfully eating their own kind isn't just absent, it's a nonstarter. When the orcs are spiriting Merry and Pippin across Rohan, one of Saruman's soldiers actually insinuates that one of his coworkers eats orc-flesh. This proves to be such an insult that it leads to the soldiers literally fighting with and killing each other. So, if it feels weird to watch orcs devouring their own kind, it's because it's not natural, even in Middle-earth.

Why didn't the Army of the Dead keep on fighting?

The Army of the Dead is one badass group of ghostly soldiers. They clear out the Black Ships that are invading Gondor in a jiffy and then completely gobsmack the entire army that's attacking Minas Tirith. They do this because they must fulfill a broken oath to fight against Sauron.

While this turns out to be a great thing for the forces of good, it does leave one wondering, why does Aragorn let them off the hook when there's still so much more fighting left to do? It's a sentiment that Gimli points out when he mentions that the lads are "very handy in a tight spot." While that's definitely true, Aragorn keeping the Army of the Dead on a leash longer than he already had would've been the wrong move. It would've spun the returning king as a power-hungry conqueror who was willing to treat others as his slaves.

As it is, in The Return of the King book, the hero dismisses the shadowy army even earlier, right after they've cleared out the Black Ships. The point to be made here isn't why Aragorn should've continued to use the Army of the Dead longer, as if he were trying to beat a video game on the hardest difficulty level. Instead, the focus should be on the fact that he's such a humble ruler that he didn't wish to abuse his control over others.

Can wizards really blast each other with their staffs?

J.R.R. Tolkien was a fan of creating a "secondary belief" within a story. In other words, rather than suspending disbelief (denying what you know is true to help you believe a story), his goal was to encourage the reader to steer into an alternate reality with the same conviction and realism that they had for their own. This desire to cultivate an inner consistency of reality is apparent throughout Middle-earth. Everything from immortal elves to overpowered Rings is presented in a believable manner. That's why when wizards start blasting each other with invisible power surges from their staffs, it can feel a bit confusing.

When Saruman and Gandalf have a wizard showdown early in The Fellowship of the Ring, it quickly feels out of place. The wizards throw each other around the room, and Gandalf is ultimately hurled up into the ceiling of the tower. The scene is off-kilter, to say the least, and it's one that Tolkien never would've condoned. In the books, Gandalf is certainly captured by Saruman, but no hint of a "wizard duel" is ever mentioned. So the next time you flip on the first part of the trilogy, feel free to look away during the wizard grudge match so that it doesn't tamper with that carefully cultivated sense of secondary belief that Middle-earth has to offer.

Why do elves show up at the Battle of Helm's Deep?

One of the strangest events in The Two Towers takes place when Haldir arrives at Helm's Deep with a troop of elven warriors in tow. Even more confusing is the fact that the Lothlorien soldier starts talking about messages from Elrond even though he hails from Galadriel's realm, which is hundreds of miles away from Rivendell.

The scene is bewildering and feels completely out of place ... because it is. Elves never show up at Helm's Deep in the original story. Does Gandalf show up with an army of Rohirrim at his back? Yes. Do Ents and their tree herds arrive behind Saruman's forces? Absolutely. But there isn't even a whiff of elvish involvement in the entire affair. And honestly, it's the out-of-place nature of the elves that makes the entire bit feel rather harebrained. The elves aren't intimately connected to (or care that much about) Rohan, either in the books or in the movies. So the fact that they would show an interest in helping the Rohirrim to the point of sending their limited population as backup soldiers — and that they would arrive within hours of a huge battle a hundred miles away, no less — is the definition of nonsensical.

How does everyone know about the Council of Elrond?

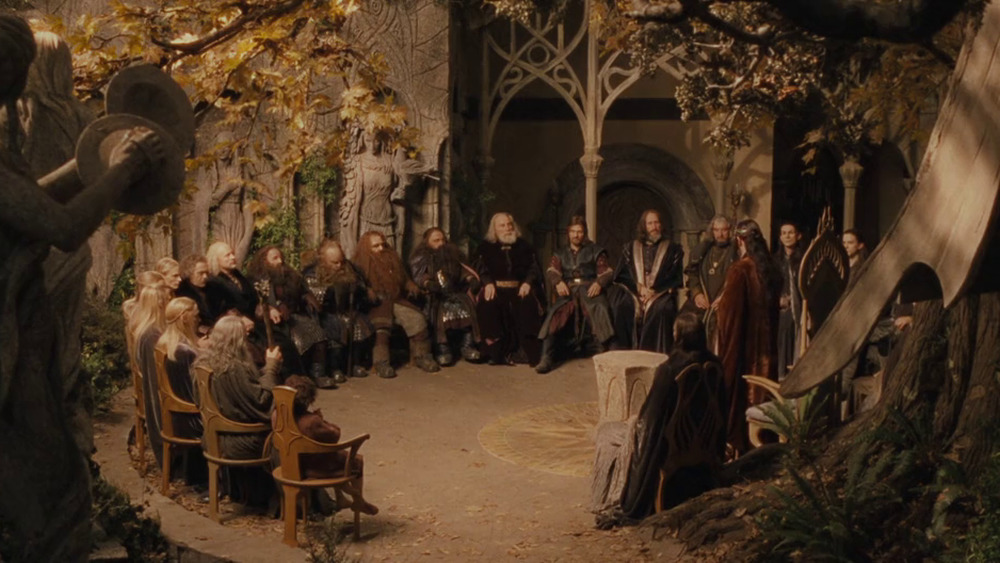

When Frodo and his companions arrive in Rivendell, they patch Frodo up and then quickly kick off the Council of Elrond. The meeting is a famous part of the story, and it features a smorgasbord of important people for the first time, such as Gimli, Legolas, and Boromir.

The question is, how did everyone know that they had to be there right at that time? We're talking about a fantasy world where the fastest way to get around is by horse — unless an eagle is willing to carry you, of course. So how did they know that they had to arrive right then? Later on, in The Two Towers film, Denethor tells Boromir that Elrond has called a mysterious meeting, but the explanation still feels far-fetched. A purposeful meeting like this would've taken months or even years to plan.

Once again, we turn to the books for clarification. In The Fellowship of the Ring, Elrond explains to the council that they must decide the fate of the Ring, saying, "That is the purpose for which you are called hither. Called, I say, though I have not called you to me, strangers from distant lands. You have come and are here met, in this very nick of time, by chance as it may seem." In other words, Elrond originally did not actively recruit a council. He simply gathered the individuals that destiny had brought together and let the event play out from there.

Why is Arwen's fate tied to the One Ring?

Aragorn and Arwen's love story is one of the themes that stretches through all three movies. The half-elven Arwen chooses mortality and a life with Aragorn, who must topple Sauron if the two lovebirds are to ever unite for the long term. The epic romance is touching, but it also gets a bit confusing at times. At one point in The Return of the King movie, Elrond tells Aragorn, "Arwen is dying," adding that, "As Sauron's power grows, her strength wanes. Arwen's life is now tied to the fate of the Ring."

This is a bit of a curveball. Sure, in a vague sense, Arwen's mortality and future with Aragorn hinge on the success or failure of the war with Sauron. But the elven lord seems to be implying that there's a direct correlation between his daughter's weakening abilities and Sauron's waxing strength.

You can chalk this one up to a pure fabrication on the part of Jackson and company. While Tolkien's original writings certainly cast Arwen as a half-elven individual who must choose between the fate of elves or men, she's never inexplicably linked to the fate of the One Ring itself. Perhaps Peter Jackson wanted to distantly tie Arwen into the storyline even more than she already was. No matter which way you slice it, though, the Arwen-Ring connection is one that never sits well within the greater narrative. Perhaps they should've left well enough alone.

Instant Ents to the rescue?

The Two Towers ends with the Ents ransacking Isengard and leaving Saruman's fortress a flooded catastrophe. Of course, in the film, this is an event that almost doesn't happen, since the Ents have their Entmoot and slowly decide that they actually aren't going to help topple the wizard from power. The selfish decision leads Merry and Pippin to trick Treebeard into taking them within sight of Isengard. Here, the father of the forest finds countless trees cut down to feed the fires of the Wizard's Vale, which, how was he not aware of that yet? Anyway, dumbstruck by the destruction, Treebeard shouts and — whaddya know! — an army of Ents is instantly by his side, and together, the group troops off to wreak some havoc on Saruman's operation.

From beginning to end, the entire series of events feels out of sync, and no wonder, too. In the books, the Ents do meet, but they come to the exact opposite conclusion. Rather than trying to stay out of the action, the Ents — who are very much aware of Sauron's anti-arboreal activities — decide to attack and do so in a planned and coordinated manner. The fact that Jackson and company felt the need to rewrite the script in such a butterfingered way is the most confusing part of the entire Entish storyline.

Cloaks that look like ... boulders?

Elvish accouterments can be magical at times. But that doesn't mean they can do anything you want them to do. Once again, we're talking about that believable nature that Tolkien found to be instrumental in shaping his world. If the fantastical elements are too outlandish, they can quickly take the believability right out of the story.

One point where this concept is on full display comes when Sam and Frodo try to sneak their way through the Black Gates of Mordor. Sam tumbles down a cliff and somehow finds himself buried up to the armpits in rubble. As Frodo tries to get him out, some Easterling soldiers come over to investigate. The hobbits manage to elude capture by hastily throwing their cloaks over their bodies, making them look like boulders.

The entire scene is haphazard and hardly believable. If you haven't read the books, it doesn't even make sense why the scene would be there in the first place. However, it turns out that this is actually a nod to the magical — though admittedly more subtle — nature of the elven cloaks that Galadriel gives the Fellowship. Throughout the story, these outer garments help the heroes in their adventures. But while their otherworldly nature does make them particularly good at disguising their occupants from searching eyes, the Lothlorien garb can hardly take on the look of rock formations that hide a wearer at point-blank range. The attempt to honor the source material was nice, but it most certainly missed the mark.

What is the 'Secret Fire' that Gandalf serves?

Gandalf's confrontation with the Balrog on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm is one of the most epic moments in all of The Lord of the Rings. Right before everything goes south, the wizard says that he is a "servant of the Secret Fire," which has led to the question, what secret fire? Is this some confidential combustible conclave of sorcerers? Is this what gives him the magic that he uses to break the bridge?

The explanation for this one starts with an understanding of just who Gandalf is in the first place. Gandalf is a Maiar, an angelic spirit who was created before the world itself by Ilúvatar, the creator of Middle-earth. In other words, he isn't a froufrou magician with a few tricks up his sleeve, nor is he a man who learned sorcery and spells. He's a bona fide spirit with otherworldly powers.

Those powers are linked to the Secret Fire. What is this fire? In Clyde S. Kilby's book Tolkien & the Silmarillion, the author claims that he had a discussion with Tolkien on this very subject. In it, Tolkien specifically stated that the "Secret Fire," which was sent to burn at the heart of the world at the beginning of creation, is a Middle-earth equivalent to the Christian Holy Spirit. In other words, Gandalf is a servant of the power behind all of creation, which is a pretty great allegiance to choose, all things considered.

How is Gimli surprised by the state of Moria?

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gimli thinks the newly formed Fellowship should speed up their journey by heading through the ancient dwarven mansion of Khazad-dûm. He promises his companions that his cousin Balin will give them a royal welcome. When they end up heading that way, he continues to lead the troop on with assurances of the fabled hospitality of the dwarves ... only to discover shortly afterward that all of the dwarves in Moria have been killed.

Why is Gimli in the dark about his cousin's kingdom? Well, it turns out that the element of surprise isn't quite so sudden in the books. At the Council of Elrond, Gimli's dad, Glóin, reports that it's been many years since they've heard from the dwarves in Moria. This clearly implies that they don't know what happened to the dwarven colony there. This should've put Gimli on his guard. Chances are his ignorant excitement in the movies can be best attributed to the producers looking to lure the audience in with a comforting sense of false security.

The Ringwraiths, Aragorn ... and a burning stick?

The Ringwraiths are some of the deadliest servants of Sauron. They hunt the Ring for him, lead his armies, speed his messages along, and generally do whatever their Dark Lord demands. Their presence is terrifying, and just one of them is more than a match for many heroes in Middle-earth. Why, then, is Aragorn able to drive five of them off of Weathertop on his own with nothing more than a sword and a burning stick?

There are a couple of reasons, actually. First off, the Black Riders may be powerful, but they have their weak spots. As primarily spiritual creatures, the Riders are particularly susceptible to the physical elements of fire and water — a fact that Aragorn is clearly taking advantage of with his burning brand. In fact, in The Fellowship of the Ring book, he doesn't even use a sword but opts for a pair of fiery sticks, instead.

While fire is helpful, though, there are some more subtle factors at work here, as well. In the source material, Aragorn points out that only five of the nine are present, implying that they operate better at full strength. At another point, Gandalf also refers to the difficulty of defeating "all the Nine at once." Additionally, the villains don't expect to be resisted, and having given the Ringbearer his deadly knife wound, they initially retreat to regroup and consider their next move.

Is Sauron really a glowing spotlight?

One of the oddest elements in Peter Jackson's adaptation is the way he represents Sauron. Initially, the villain is spot on, shown as a towering figure clad in black armor. At the end of the Second Age, though, the One Ring is cut from his finger, and he loses his physical form as a result. This is complicated, but suffice it to say that Sauron is a primarily spiritual creation, and his taking a physical form requires time, effort, and power.

Over the 3,000-year-long Third Age that follows, Sauron slowly takes on another new form. He initially becomes known as the Necromancer — the shadowy form he's shown inhabiting during The Hobbit. The next thing you know, he's a glowing, fiery eyeball on top of a tower in Mordor.

This idea of the Dark Lord taking the shape of an optical organ is strange, and as might be guessed, it's nothing like the book version of the villain. Sure, the "eye of Sauron" is referenced, and his malicious glare shows up when Frodo looks in the Mirror of Galadriel. But Gollum also reports seeing Sauron's hand with its four remaining fingers, as well, indicating that the Dark Lord is far more than a fiery eyeball that looks like it's illuminating a Sunday Night Football game.

Why does Frodo need to leave Middle-earth?

At the end of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo has to board a ship, and he heads into the West. While sad, the scene can also be a bit confusing, especially for those who haven't read the books. Why does Frodo need to leave? The good guys won, right? He's all healed up and rested. What's the big deal?

If you dig a little deeper, though, it turns out that, while the world is okay, Frodo isn't. In fact, the hobbit hero ends up sacrificing far more of his own internal health and stability than is shown in the movie. It's part of what makes him such a powerful person under that humble hobbit exterior. All that to say, while he's the only individual with enough grit and determination to carry the One Ring all the way to the Cracks of Doom, the adventure takes a serious toll on him.

After the Ring is destroyed, Frodo continues to show long-term effects from his experience. His knife wound on Weathertop gives him annual aches and pains, and he struggles with a lingering inner regret that the One Ring — which did a number on his inner conscious for so long — is truly gone. In The Return of the King, he tells Sam that he has been "too deeply hurt," adding, "I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. ... When things are in danger: some one has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them."