Civil War Movie Explained: Breaking Down The Convoluted Politics

This article contains spoilers for "Civil War"

"Civil War," a sci-fi movie about a second civil war dividing America — released in an election year where America couldn't be more divided — stakes an early claim as the most controversial movie of 2024. While the film has enjoyed wide acclaim from film critics and looks to be a major success by the standards of indie distributor A24, some people fear its depiction of partisanship turned to violent extremes, including a climax involving a military attack on the nation's capital, is simply too realistic and plausible to be enjoyed as entertainment. In contrast, others have questioned how realistic or meaningful the movie can be when looking at the seemingly implausible details of its imagined political situation.

So what is all the fuss about, and what is "Civil War" trying to say about our current moment? Writer-director Alex Garland doesn't make answering your questions easy, refusing to offer up direct exposition and framing the film from the perspective of unbiased journalists. But just because the film keeps the details about the war obscured doesn't mean they're not there, and just because the conflict in the film doesn't directly map to present day partisan alignments doesn't make its messages about journalism, authoritarianism, and armed resistance "apolitical" ones.

From our best attempt at understanding its complicated (and largely unexplained) backstory to the difficult feelings stirred by its unforgettable ending, here's our explainer for all the spoiler-y details of "Civil War."

What you need to remember about the plot of Civil War

"Civil War" takes place at some point in the not-too-distant future (or perhaps in a present-day alternate universe?), with the United States no longer united but split into four warring factions. Dropping the viewer right into the middle of the conflict, the movie follows four journalists traveling from New York to Washington, D.C., where the Western Forces of Texas and California are attacking the Loyalist government.

Reporter Joel (Wagner Moura) seeks an interview with the Loyalist President (Nick Offerman), while the renowned photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst) captures every horrific sight along the way. Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), a young amateur photographer who idolizes Lee, tags along despite the danger, as does Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), an older respected reporter whose physical health puts him at a disadvantage in high tension scenarios.

Along their journey, Jessie gains experience photographing battles and executions, her initial terror giving way to a perverse thrill in doing the work as she learns to follow in Lee's emotionally detached footsteps. Stops on their trip include a refugee camp, a sniper showdown on a golf course, and one eerie village – like something out of "The Twilight Zone" – that pretends the war isn't happening. Approaching D.C., a cheerful meet-up with some Asian journalist friends (Nelson Lee and Evan Lai) gives way to a tense, violent hostage situation with a xenophobic soldier (Jesse Plemons). Sammy rescues his team and drives them to safety, but dies from bullet wounds.

What happens at the end of Civil War?

In the final act of "Civil War," the road trip movie shifts gears into a large-scale action film. Lee, Jessie, and Joel are embedded with the Western Forces army as it invades the capital. Word is spreading that the President is already preparing his surrender, but that doesn't stop the WF from going in full-force with helicopters and guns ablazin', even going so far as to blow up the Lincoln Memorial as they attack. When the soldiers and journalists eventually make their way through the combat zone and into the White House, a government official offers terms of surrender — only to be killed outright. With the way the fighting has escalated, peaceful negotiations are treated as no longer possible.

In the ensuing firefight through the White House hallways, Lee sacrifices her life to save Jessie's. As foreshadowed by an earlier conversation between the two photojournalists, Jessie ends up photographing Lee's moment of death as she rescues her. The WF finally reach the President and are ready to kill him, but Joel interrupts the assassination — he needs a quote for his article. The President begs, "Don't let them kill me!" The ever-"impartial" journalist responds, "That'll do," then steps back and lets the soldiers do their dirty work. Jessie snaps her shot of the killing in what ends up being the final image of the movie before the credits, as "Dream Baby Dream" by Martin Rev and Alan Vega plays in the background.

So what was the war about?

"Civil War" never states how its war started, nor which side fired the first shots. Many characters, both those trying to avoid the war and those fighting within it, simply won't talk about politics, and everyone else is so familiar with the state of the world that they have no need to spout exposition about it. From context clues, particularly through Joel and Sammy's conversation about what questions would be best to ask the President in an interview, we can figure out some of the main issues this war is being fought over.

Put simply, the President is a fascist. He's on his third term (implying either a rewriting or subversion of the Constitution), he's gotten rid of the FBI (recalling certain authoritarian calls by criminally-suspect politicians to destroy the "Deep State"), he's using drone strikes on his own citizens, and he deems members of the press as "enemy combatants."

Other political factors either contributing to or resulting from the war also show up. Protesters on the street beg for water, only to be met with police brutality. The American dollar has completely collapsed in value; Lee has to pay for gas in Canadian dollars. The sequence with the soldier played by Jesse Plemons adds a clear tenor of alt-right xenophobia to at least one side of the conflict: while the soldier's alignment is never directly stated, the states he gives his approval of as the "real America" offer the clear implication that he represents the Loyalist agenda.

How did Texas and California join forces?

Perhaps the single most argued-about line in the "Civil War" trailer on social media was the reveal of "the Western Forces of Texas and California." At present, California consistently votes Democratic while Texas keeps electing Republicans, so many find the concept of such a team-up unbelievable. Does the movie make this pairing more convincing?

Sort of, although those who lack Alex Garland's faith that red states and blue states would find common ground in the face of a dictatorship will have to suspend their disbelief. At the very least, the present-day unlikeliness of the alliance keeps the film in the realm of a sci-fi thought experiment rather than a prophecy of the near future.

Lending some degree of semi-realistic believability to this fictional scenario is the fact that groups within both Texas and California have advocated for secession in the past decade, and that they're likely two of the only states with the population, economic strength, and technological resources to even stand a remote chance in a fight with the federal government. In addition, "red state/blue state" lines are always changing over time: right-wing activity is growing in influence within alleged liberal strongholds of California, while shifting demographics could conceivably push Texas to the left.

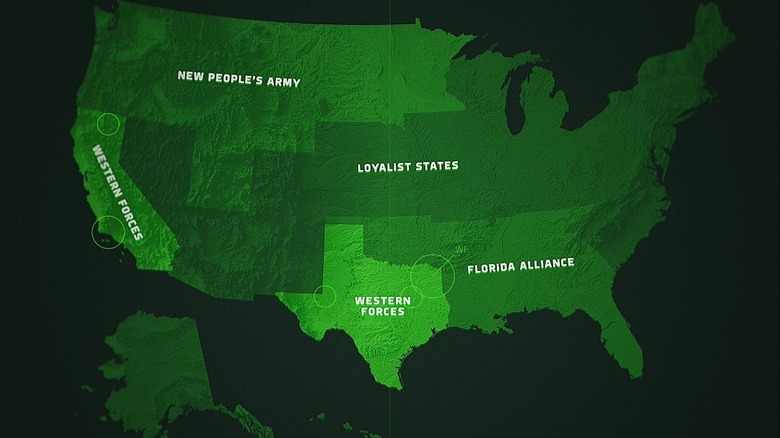

What are the New People's Army and the Florida Alliance?

While only the Loyalist States and Western Forces take center stage in the action of "Civil War," maps and throwaway dialogue reveal the existence of two other breakaway factions connected to the conflict: the "New People's Army" in the Northwestern states and the "Florida Alliance" in the South. The nature of what these specific groups are fighting for, and what political differences stopped them from joining the Western Forces, remains unexplained.

A line referencing "Portland Maoists" hints at the New People's Army possibly being a far-left group (it also shares its name with a Filipino Communist army), though the idea of Utah and Idaho turning Communist might make the California-Texas alliance look like even more of a plausible proposal in comparison. Perhaps this front of the war was the site of the "Antifa Massacre" that Lee became famous for photographing?

The Florida Alliance, meanwhile, receives even fewer hints about its leanings and reasons for secession. Interestingly, when Joel mentions being from Florida when questioned on the type of American he is, Florida gets defined as part of "Central America," a phrase which in the present day would refer to countries south of Mexico and north of Colombia. One suspects that the real reason for making the Florida Alliance its own separate, ignored entity is for the purposes of taking the majority of secessionist states from the real American Civil War out of the picture for this fictional one.

Is New York fascist?

Perhaps just as controversial as the decisions of which states seceded in "Civil War" are the choices as to which states stayed. Notably, the whole Northeast, including the protagonists' main residence of New York, has stayed loyal to the fascist government, a plot point certain to raise questions about what happened to the former liberal stronghold. In an interview with The Atlantic, Alex Garland offered up the possibility that changes in political alignments occurred as a result of the President's own politics changing between his first term and his third: "He may be a fascist at the point we meet him, but he presumably in his first term didn't say [that] ..."

One can also read the opening sequence in New York City as one of top-down repression, with concepts of political norms and "law and order" getting twisted to maintain an illusion of a status quo even when things are not normal. Better protections for journalists (the buildings where they hold their social gatherings have backup generators, allowing them to ignore regular blackouts) might serve as a way for NYC to believe it's still more progressive than D.C., even if it's ultimately on the capital's side.

How are we supposed to feel about the ending?

Keeping with the emphasis on journalistic objectivity, Alex Garland does not tell the viewer how to feel about the ending of "Civil War." The basic premise of "What if anti-fascists had to do their own January 6th and succeeded at it?" is sure to inspire complicated emotions from viewers of all political persuasions. Garland's overall agenda for the film is to deliver a clear "war is hell" message, but when it comes to the ending, even those feelings become more complicated: are we to view the film's concluding act of violence as another abomination, a tragic necessity, or something to celebrate?

With a few tweaks in execution, it would be easy to turn Joel's moment of tacit approval towards the assassination into the satisfying ending of a Quentin Tarantino revenge movie for Resistance Liberals. Garland won't let himself cheer — at a Q&A following a New York press screening, he described the film as an attempt to "modulate" rather than give in to the anger he feels about politics — but the ending offers a sense that he can't totally deny the subconscious ugly appeal of such vengeance. The final musical choice of "Dream Baby Dream" is ironic in its discordant cheeriness, but also serves an acknowledgement that the film's conclusion is going to be a dream come true for some members of the audience. You'll have to make up your own mind as to what message, if any, is being delivered.

What is the film saying about journalists?

At the South by Southwest premiere of "Civil War," Alex Garland described his film (via Spectrum News) as a "love letter to journalism." At a Q&A following a New York press screening, he called the movie a reflection of what he sees as a weakening of the press's power, saying, "I spent a lot of time wondering if Woodward and Bernstein and The Washington Post had been investigating Nixon now, or four years ago, which would be the same as now, would that story have led to his government ending? ... I'm not sure it would."

While "Civil War" is respectful of journalists, it might also inspire some to question the nature of this brand of war journalism. The way Jessie has to grow increasingly emotionally detached, to the point of near-sociopathy, in order to pursue her career goals, and the way even the death of the person she loves most becomes more fodder for her work, paints a complicated picture of the profession.

The film also makes something of an argument for the impossibility of true journalistic objectivity when one gets close enough to the action. In order to get "both sides" of the story and maintain the illusion of impartiality, Joel has to interrupt the President's execution to get a quote from him. This ironically puts him in a conundrum in terms of objectivity: he can either follow through on the President's request and take one side, or let the execution commence and take another side (he does the latter). Either way, he can't claim to be truly separate from the action.

What the actors have said about the ending

At the aforementioned New York press screening Q&A, actors Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny shared their thoughts about the ending of their characters' journeys. When asked what it was like to act out the moment of Lee's death, former "Spider-Man" star Kirsten Dunst answered, "There's so many feelings you can take away from this film ... but [Lee] has to carry on and get the story ... Passing the torch is what she has to do." She praised the presentation of the moment for its "subtlety" and "not being too emotionally forceful," and said this handing-off-the-baton ending felt "kind of like a destiny" for the characters.

Spaeny found the experience of filming the scene somewhat surprising even with her preparations. She explained that the movie was shot in chronological order, so she "knew there was going to be a passing of time, but I didn't know when it was going to happen ... It was interesting to see how I would just walk on set and go, 'this is the day she takes that turn.' I didn't know what the ending was going to be until I got there."

What happens next?

it's safe to say that "Civil War" is a movie no one is going to want a sequel for. By the end of the movie, half of the main characters and many of the supporting cast are dead, and the central war is over in the most definitive way possible. The only way the story could continue would be to delve into follow-up conflicts, perhaps its equivalent of the Reconstruction era, but that would require digging deeper into the specific political weeds of the setting in ways that would be at odds with Alex Garland's commitment to leaving this world open to interpretation.

Befitting that intention, viewers will leave the film having to imagine for themselves what comes next for America after the film cuts off. Curiously, the movie ends right with the death of the President, not even offering a moment of reflection or uncertainty for the characters themselves to ponder what comes next. History teaches us that the end of one war is never going to be the end of the political conflicts that caused the war, and what it would take to rebuild a country that's so clearly broken is something people will have to figure out themselves after leaving the theater.