What Crime Procedurals Always Get Wrong About The Law

Suspension of disbelief is usually required for people to enjoy a large majority of the fictional stories that air every day. Of course, stories aren't real-life, and they sometimes need a little leeway on reality. With crime procedurals, though, it is very easy to see technical and legal institutions operating on screen and assume that it's a pretty direct reflection of reality. After all, so much of the law and its systems are complex and not studied widely in school, there isn't much of a standard level of knowledge that can be assumed of any average citizen. In fact, some people's main exposure to the legal system can be through crime procedurals.

In Season 9 of "Last Week Tonight with John Oliver," Oliver's main segment centered around the cultural kahuna that is "Law & Order" and the world that's been built around it by TV producer Dick Wolf. Oliver talked about many important issues surrounding Wolf's cultural contribution to the perception of law enforcement and America's legal system, his main point being that audiences need to be better equipped to understand the difference between entertainment and reality.

Even though some shows, like "Law & Order," have consultants who work in the legal and law enforcement fields (as Oliver explained in his show), the most important thing to writers and producers is not to present what is most accurate, but rather what is most entertaining. Here are the things that crime procedurals almost always get wrong about the real-world legal system.

Restraining orders

One legal trope that is constantly used on all types of television shows — not just crime procedurals — is the restraining order. From references in shows like "Law & Order" and "Criminal Minds," and even sitcoms like "New Girl" and "Community," one might assume that it's pretty easy to file a restraining order against someone. This is categorically false, even when you take into consideration the fact that every state in the US has different laws surrounding orders of protection, restraint, and harassment.

In most states, whether a restraining order (aka a protection order) is granted is up to a judge. Most orders of protection make it illegal for the served party to interact with the person who filed the order, but because of that, there are very strict requirements that must be met before an order will be granted, as can be seen in a document prepared by the BWJP.

People can't just go get a restraining order because they're annoyed with someone. The person filing for the protection order must often provide proof that their well-being is in danger. Most states offer protection orders for harassment that isn't necessarily life-threatening, but for that to be granted, you need to record a long pattern of harassment and repeated incidents. It's a much more complex legal tool than TV would have audiences believe.

Hospital translators

You've probably seen this plot on both crime and hospital procedures. Someone checks into the ER with mysterious injuries — usually contusions, broken bones, etc. That patient doesn't speak English, so the doctor talks to their parent, spouse, or kid, who takes it upon themselves to translate for the injured person. This usually leads to a lot of drama and misunderstanding, from anywhere between a parent being unable to tell their child the truth about what's wrong with them to an abuser who is manipulating the doctors in order to avoid getting in trouble.

The thing is, hospitals are legally required to provide translation services to any patients that do not speak English. Thanks to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it is considered discriminatory for any hospital that receives federal funding under Medicaid to deny translation to a patient, as explained by language service providers NWI Global. Even if a hospital happens to forgo federal funding (which is rare), every individual state government has a similar law in place at the regional level.

Many nonprofits that work to prevent and respond to domestic violence and intimate partner violence have lobbied to make sure that hospitals and police stations are held accountable to these laws. This is because it can often be the case that a major way in which an abuser maintains control over their victim is by preventing them from learning English or how to communicate with many folks outside of their home or social circle.

Lab expedience

Almost every crime procedural has some kind of veritable tech or scientific genius on its criminal investigation team. Whether it's Abby Sciuto from "NCIS" or Penelope Garcia from "Criminal Minds," there's usually one all-knowing, crime-solving machine who provides a brawny detective team with seemingly all of the information it needs.

In reality, criminal investigations take a lot of time and can involve teams with dozens of people working in dozens of different specialties. Even when there's been a homicide and a forensic lab has been instructed to rush a test for evidence, it usually takes at least a week to get results. And again, that's only if it's everyone's top priority to solve a case, which usually only applies to those that are specifically high profile.

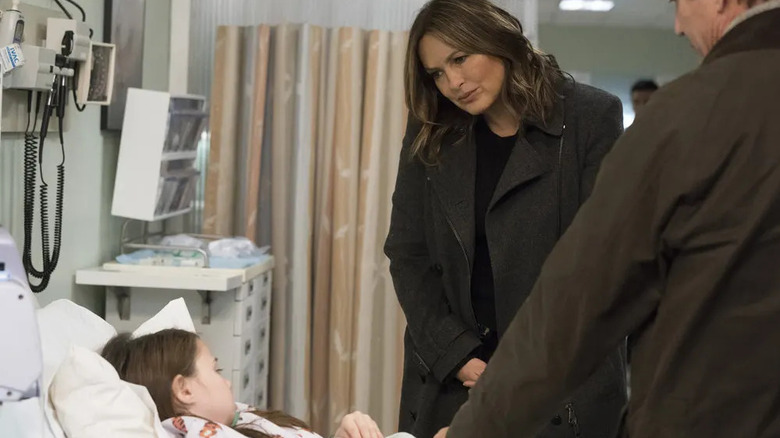

You may have heard of the forensic DNA testing backlog that has been brought to the forefront of public attention over the past decade by organizations such as RAINN, especially as it regards the processing of SAFE (Sexual Assault Forensic Evidence) Kits. In fact, "Law & Order: SVU" actress Mariska Hargitay has also helped raise awareness for this issue. According to OJP, these backlogs, plus the continual strain of new cases placed on an overburdened system, mean that things like DNA analysis, data science investigation, and other technical work can take specialists months to address.

Prison release time

While "Brooklyn Nine-Nine" is a workplace sitcom first and foremost, it is also a crime procedural that follows the struggles of a police precinct and is thus prone to the same kind of mistakes as any other show that centers around the American legal system. At the end of Season 4 of "Brooklyn Nine-Nine," detectives Jake Peralta and Rosa Diaz are wrongfully convicted of a series of violent bank robberies committed over the course of several months and are sent to prison.

In the first few episodes of Season 5, Rosa and Jake, thanks to the hard work of their fellow officers, are exonerated. Which was great! Still, Jake's life is in pretty imminent danger thanks to his betrayal of Romero, the most notorious drug dealer in his prison. The first attempt on his life by Romero is thwarted, but it is guaranteed to happen again as soon as Romero gets the chance. It's a good thing that Jake is on a TV show and therefore was freed from prison immediately.

In reality, even when investigators succeed in finding DNA evidence to prove a convicted person's innocence, it still takes a very long time to secure that person's release. Vanessa Potkin, a director of post-conviction litigation at The Innocence Project, explained to How Stuff Works that it takes, on average, about seven years after the discovery of new evidence for someone to be let out of prison — which is pretty horrific.

The insanity defense

It would take a long time to list every television show or movie that has ever had a character plead insanity when charged with a crime. However, according to Justia, the defense is used in fewer than 1% of criminal cases that go to trial and is usually only successful in a fraction of those uses over the course of a year. Every state in America requires that a defendant meet pretty specific requirements for being considered insane, and it's not easy to convince a jury that someone is so far out of their right mind that they can't be held responsible for their crime.

For TV writers, it probably feels like the perfect way to allow a character to escape justice and therefore prevent a satisfying resolution for the detectives and lawyers working to prosecute a case. It gives their characters a chance to be competent at their jobs and still retain the angst that comes with feeling like a bad person is getting away with doing a bad thing. Still, it's important to note that being found innocent by way of insanity is not a get-out-of-jail-free card.

A&E did a deep dive into maximum security psychiatric facilities and they are definitely more comfortable and hospitable places than regular prisons, thanks to mental health treatment advances over the past century. That said, the people living in those places are still incarcerated, and many of them die never having been released.

Miranda rights

There are plenty of things that TV shows such as "American Rust" get wrong about police work, but one of them has to do with the omnipresent Miranda rights speech that nearly every onscreen cop has delivered at one point or another: "You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to speak to an attorney, and to have an attorney present during any questioning."

There are probably a lot of people out there who are not and have never been cops that could easily recite the speech thanks to its prevalence in crime procedurals. In addition, there have been many plot lines on crime procedurals and in cop movies wherein a case against a suspect is completely ruined because the arresting officer didn't give them their Miranda rights or did so incorrectly. It is possible to ruin a case in that way, but it's not guaranteed.

Miranda rights only need to be relayed to someone being arrested if law enforcement officials are planning on interrogating them. If a suspect is arrested due to overwhelming evidence that they committed a crime, it's entirely plausible that the police don't need to interrogate them or get a confession.

Crime scene free-for-all

There's a very good chance that the scene following the opening credits in a crime procedural will take place at the scene of whatever crime the protagonists are investigating that week. Often, creative establishing shots portray an investigative area featuring dozens of technical and police personnel performing different tasks relating to evidence collection, scene documentation, and crowd control. On top of that, we often see at least two or three extra folks just standing around and listening to the leads discuss their first impressions of the crime.

In reality, crime scenes are handled much more delicately and carefully. Any person interacting with a scene has the potential to contaminate or obscure important evidence, and every new person that enters is a whole new set of variables that need to be accounted for. People sweat, sneeze, stomp, trip, gesticulate, and practice any number of normal human functions that are usually not even consciously driven. No matter how careful someone is, there is always a chance for human error.

Real crime scenes are usually attended by as few people as possible to limit that inevitable contamination. Also, people handling evidence at a crime scene can't just call things good with one pair of gloves. As soon as they touch something with a pair of gloves, those gloves are no longer 100% effective in preventing cross-contamination of evidence.

Jury selection

In the Season 3 episode of the show "Bull" titled "Jury Selection," the main character, Dr. Jason Bull, is called up for jury duty. If you aren't familiar with "Bull," it's a CBS law procedural wherein Jason Bull and his team consult with legal teams to help them with strategic jury selection and, hopefully, win their case. Never, in a million years, would the defense or prosecution want someone like Dr. Bull on their jury.

There are many law firms in America that have pages on their websites dedicated to explaining the importance of jury selection in a trial. Jury selection involves a large number of citizens being called for a process known as voir dire. Voir dire, which literally means to "speak truth," is a period in which lawyers and judges may pose questions to prospective jury members to determine whether they have any biases or conflicts of interest that would prevent them from making a fair determination in a trial.

There are a lot of reasons that someone can be rejected for jury duty, but one of the most prominent is certainly holding a profession that has anything to do with law enforcement or judicial proceedings. Often, lawyers don't want someone with a background in forensic work on their jury because they know those people will not be easy to manipulate. The American justice system is such that lawyers want to select a jury that will move together toward the decision their client is hoping for — not a jury with specialized knowledge about the criminal case at hand.

Going to trial

The way a show like "Law & Order" functions is by first showing law enforcement officials investigating one crime over the course of a week or so, and then passing the case onto the District Attorney's office. There, one or two snappy young lawyers (or wise, older lawyers) take the bull by the horns and build a case against the arrested suspect. It's formulaic, and thus comforting to viewers, but the work of a cop or a district attorney is hardly ever that linear.

Many detectives and prosecutors have caseloads that leave them working on at least half a dozen cases at a time. It's also not uncommon for caseloads to reach triple digits, and according to NOLO, at least 90% of criminal cases are resolved before they reach the trial phase. Defense attorneys, especially, are often wary of trials by jury and often believe that a plea deal will provide their client with the best possible outcome while removing any uncertainty, no matter if their client is innocent. But to be fair, crime procedurals would be a lot less fun if most episode/case resolutions were reached by two lawyers chatting behind closed doors.

Objections

Some of the most dramatic and unpredictable scenes ever shown on screen have depicted lawyers having it out in a courtroom. It's exciting to see people make a case using only their intellect, and as well to see a particularly adversarial dynamic between two sides of a case or even one side of a case and the trial judge. In real life, courtroom trials are some of the most painstakingly regulated aspects of the criminal justice system.

In a Wired video series on television accuracy, a lawyer explains that objections are taken much more seriously in real life. When a lawyer yells objection during a case, the opposing litigator is required to immediately stop their questioning until the judge rules on the validity of said objection. Obviously, if TV lawyers were to stop talking every time there was an objection to their behavior in court, we'd miss out on a lot of impassioned moments, but there are a lot of regulations for lawyers and what they can and cannot do during a trial.

Courtrooms are not a debater's version of the Wild West, unlike what audiences might think, and many lawyers would face a lot of professional consequences for consistently displaying the bad practice that is par for the course in TV courtroom scenes.