Things That Happen In Every M. Night Shyamalan Movie

The central theme of M. Night Shyamalan's career can be summed up with one phrase: Expect the unexpected. This is as true of the notorious plot twists his films are known for as it is of his surprising fall from grace in the eyes of many critics and some less appreciative fans. The man who was once considered the next big thing has fallen short of those lofty expectations a few too many times, and Hollywood isn't quick to forget it.

No matter how they are received, though, Shyamalan's films remain reliably true to a number of trademark elements. Maybe coming to expect a twist ending, as so many do from his movies, makes it all a little less satisfying. But when you look at how uniquely (and sometimes artfully) he orchestrates each one, no matter how many times he's done it, it's hard not to be impressed. In each film, Shyamalan explores a new take on color symbolism, an inventive use of the camera, and a number of other intriguing approaches. Moreover, Shyamalan deserves respect for the way he constantly challenges and improves himself as a filmmaker and the people he works with. With that in mind, let's take a moment to examine the details, symbols, and artistic approaches that happen in every Shyamalan film.

Shyamalan is almost always in his own movies

There are a couple of actors who have appeared in multiple Shyamalan films. One of the first to come to mind is Bruce Willis: Recall his iconic role in 1999's The Sixth Sense, followed by 2000's Unbreakable and its subsequent sequels, 2016's Split and 2019's Glass. Then there's Joaquin Phoenix, who appeared in 2002's Signs and 2004's The Village.

One of Shyamalan's other top collaborators is, in fact, himself. Not only does he tend to write, produce, and direct his own movies, he is also known for acting in them. These roles are usually pretty small: In 2010's disastrously bad The Last Airbender, he showed up as an uncredited firebender in a prison camp, while in 2008's The Happening, you can hear his voice on the phone as Joey.

Shyamalan has given himself bigger roles as well, but they haven't always gone so well. In fact, one of the major public complaints aimed at 2006's Lady in the Water, which was largely panned by critics, is what many perceive as Shyamalan's self-congratulatory role: He played a writer who saves the world with his grand ideas. Shyamalan does best when he plays roles like his one in Signs, in which he portrayed the man responsible for the car accident that kills the protagonist's wife. Though it's not one of the movie's major speaking parts, this role does launch the protagonist's entire backstory.

Shyamalan finds the unknown in the mundane

What's the scariest thing about your hallway? You probably can't think of anything — they're pretty mundane spaces. This is why, if you did find something terrifying in your own hallway, it would be twice as scary: Fear has invaded your home, one of the places you feel safest. It's infinitely more jarring and violating to see something spooky in a familiar place than it is to see it exactly where you already expect it.

Shyamalan's approach to horror evokes fear, as he put it in a 2019 interview with NME, by "creating the unknown" and placing it in settings that would normally be unthreatening. He wants to keep fear rooted in reality, where we can really feel it: It's a lot more chilling, he notes, "if the kid in The Sixth Sense is walking down a hallway that looks like the hallway that you have to walk down to get to the bathroom every morning." With that established, the fear Shyamalan evokes doesn't just live in a single shot — it lives in the character's safest spaces, and, by extension, the audience's.

In a discussion with Skylife, Shyamalan elaborated on "the unseen and the unknown" in Indian culture, and how it brings a unique richness to his stories. He's always been curious about what's "behind the curtain," and his impeccable sense of pacing both lowers that drape and pulls it back at just the right moment.

Colors mean more than you think in Shyamalan's films

While there are plenty of details in Shyamalan's movies that you might miss if you aren't paying strict attention, there's one particular device the director uses to openly spell things out — or, more accurately, color them in.

In The Village, the color yellow is explicitly worn as protection (known among the residents as the "safe color" that allows passage into the forest), while bright red cloaks are worn by the entities that threaten the community. Of course, the safety yellow truly represents is that of innocence, which is why children have been able to enter the forest and come out unharmed: It's not an accident that you don't see any of the elders ever wear yellow, nor that they are the ones who don the red cloaks to create their destructive monster myth. A cloistered settlement formed for survivors of the crime-induced deaths of loved ones, the village itself is a study in the way that trauma robs us of our innocence, just as Ivy is in turn robbed of hers when she discovers Lucius' murder.

In The Village, those key shades of yellow and red are staged against the backdrop of a dreary Pennsylvania forest. But in films like Unbreakable, they are contrasted with the murkiness of flashback sequences. In a sea of monotone garb, chief characters wear the classic purple of comic book villains everywhere, even before their evil natures are revealed.

Shyamalan's horror hinges on human grief

The collaboration between grief and horror is a subject Alfred Hitchcock, whom Shyamalan names as a major influence, often examined. Consider his 1960 thriller, Psycho – If you can't properly grieve your mother, you might just become her, a la Norman Bates. Both of these directors' films have always been about more than just horror. In fact, their horror hits harder because it's predicated on a vulnerability most of us have felt. Fear of death is primal, and grief comes from a deep place of human connection that is uniquely painful.

Shyamalan's first big hit, The Sixth Sense, doesn't just center around the theme of death — it also creatively explores the idea of moving on. But, contrary to what most audience members would expect, this study in grief comes from the other side of the grave, though viewers don't know it until the infamous twist at the end of the film arrives. Explorations of the fear surrounding death are nothing new, but horror films often forget to look at the fear that accompanies loss and even survival. Shyamalan's films break the mold in this regard. Recall Signs, a movie about aliens in which the extraterrestrial aspects take a backseat to the very raw and human experience of grief and its impact on faith and family.

There's a family dynamic in most Shyamalan movies

Family relationships and dynamics permeate a lot of Shyamalan's films. Believe it or not, the famed director even has some experience making all-ages family flicks: Shyamalan co-wrote the film adaptation of E. B. White's 1945 children's novel Stuart Little, which came out the same year The Sixth Sense was released. In the latter movie, the relationships between Bruce Willis' child psychologist character Malcolm and the patients he treats form the backbone of the narrative, highlighting the influence adults hold in one's formative years and the hapless father figure position Malcolm finds himself in. His fraught navigation of this position is the impetus for his death and the basis of his relationship with Cole in his afterlife.

This theme of family pops up all over Shyamalan's filmography. It's a central part of 2015's The Visit: Their mother's familial estrangement is the reason Becca and Tyler find themselves in their bizarre and dangerous predicament. Signs is about a father struggling to protect his children against both the grief of losing their mother and extraterrestrial forces. The relationship between Ivy and her father is pivotal in Signs, as is his eventual revelation to her that the forest creatures are a hoax. The broken marriage in Unbreakable is an important window into the protagonist's life.

In a Shyamalan film, the devil is in the details

Shyamalan is extremely detail-oriented, a fact made evident by his films' many Easter eggs, references, and moments of sly foreshadowing. Anything you see in one scene might become important later. Recall the moment in The Sixth Sense when Cole utters his famous line, "I see dead people," followed by a camera pan to Malcolm. This pan isn't just happening to capture his reaction to Cole's words: It's also because those words are referring to Malcolm himself.

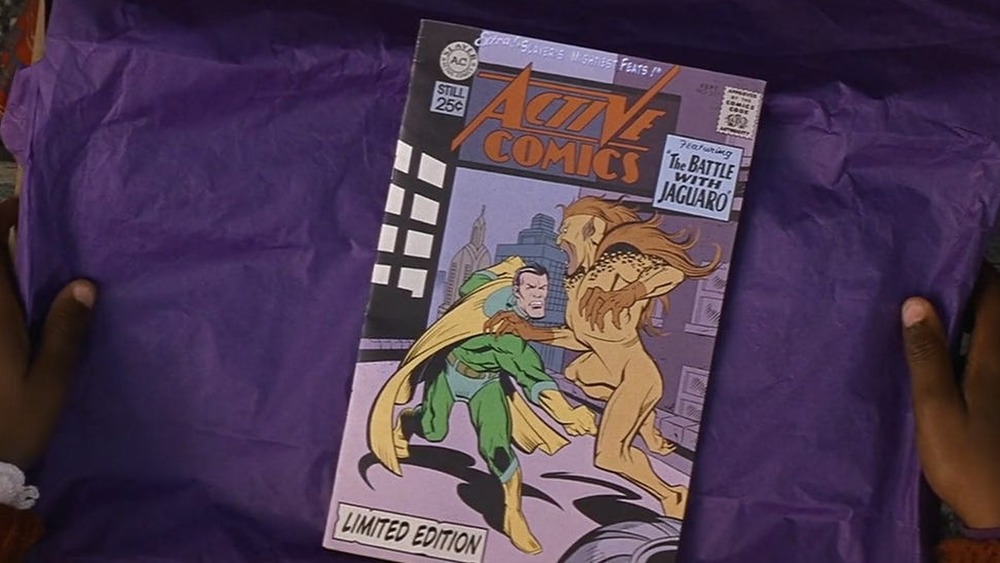

Some of Shyamalan's finest uses of nitty-gritty foreshadowing can be found in the ways he carefully connects the films in the Unbreakable trilogy. The reveal of the films' relationship to each other is much less shocking when you take the time to examine their smallest details. For example, the first comic book Elijah Price receives as a child shows a hero in green, the established color for David Dunn in Unbreakable. The green-clad figure fights a villain dressed in the Beast's characteristic yellow from Split, foreshadowing their meeting in Glass. In that film, Shyamalan even includes the scars on the Beast's body that he sustained when Casey shot him in Split. The director's attention to detail allows him to achieve incredibly convincing worldbuilding in this story, and so many others.

There's always a twist in Shyamalan movies

You saw this one coming: In just about every Shyamalan movie, there's a major twist. There are a few exceptions, like The Last Airbender, which is an adaptation of an existing property, rather than an original concept — though that film arguably boasts the stunning twist of completely botching its beloved source material.

It was the "Shyamalan twist" that first made the director famous in 1999 with The Sixth Sense, which shocked the world by revealing that the main character had been dead the whole time. As we've now come to expect a twist in his films, each new surprise must be more and more inventive in order to be compelling. For the most part, Shyamalan delivers, giving us twist endings that not only shock but also seem obvious in retrospect. That's a pretty ridiculous balance to have to strike.

In Unbreakable, Mr. Glass reveals himself as the villain in a chilling sequence in which David Dunn sees Glass' memories of committing a number of mass murders. At the end of The Village, we find out that the monsters in the forest are really the settlement elders, and that the village exists in isolation in modern times, rather than in the 19th century. This twist was largely disappointing to critics, but 2015's The Visit marked a return to classic Shyamalan goodness with its surprising and well-received conclusion.

Elements of Shyamalan's childhood and history make appearances

Not only does Shyamalan himself appear in many of his own films, but he imbues them with a lot of personal history as well. Many of the director's films are set or filmed in Pennsylvania, where he grew up after moving to the United States with his family at six weeks old. Between the state's historic major cities and picturesque countryside, you can shoot just about anything there, and Shyamalan certainly has. In fact, only his first film, 1992's Praying with Anger, was not shot or set in Pennsylvania.

Of course, it also helps that Shyamalan's home state offers a generous tax credit to filmmakers who choose to shoot their projects there: Projects can get a 25 percent break if they spend over 60 percent of their budget in the state. Shyamalan has been a major advocate of this tax credit and has called Pennsylvania "one of the greatest places to shoot in the world." Sure, he's a bit biased — but you can't deny his movies have great scenery.

All of Shyamalan's movies are self-described journal entries

Shyamalan's first two films are directly connected to his childhood. This makes sense, as he described all his movies as "journal entries of where I am in my life" in a 2020 interview with The Ringer. For example, Abigail Breslin's character is five in the movie Signs, which was made and released around the time Shyamalan's own daughter was five years old.

Shyamalan's lesser-known first two films are even more explicitly tied to his life. His first film, 1992's Praying with Anger, is a semi-autobiographical film about a young man coming of age between the competing values of the United States and India. His second film, 1998's Wide Awake, is the only family feature he got to make before horror audiences commandeered his services. In a 1998 interview with the Sun Sentinel, Shyamalan noted that he had always wanted to make a movie about his experiences in Catholic school.

Even when his films aren't such obvious adaptations of his own experiences, Shyamalan still enriches his characters and plots with elements of his life. This is especially evident in Split, which is about a man with dissociative identity disorder. For this film, Shyamalan has noted the influence of his wife's work as a psychologist.

Stars step outside their comfort zones in Shyamalan's movies

In Shyamalan's movies, you'll often see talented actors being pushed out of their normal range. Shyamalan challenges his actors to find the emotional depth and humanity in the supernatural and the horrific, and what results is a compelling union of these elements and a learning experience for the stars involved.

In fact, in one film, Shyamalan helped bring an actress not just out of her comfort zone, but into the spotlight for the first time. The Village includes Bryce Dallas Howard's breakout role: She played Ivy Walker, the blind daughter of the Chief Elder who founded the village as a haven from the modern world. After this role, she went on to become an A-lister, appearing in major films like Spider-Man 3, Jurassic World, and Rocketman.

In Signs, Shyamalan tasked Joaquin Phoenix with both comic relief and emotional intensity, as the camera cuts to his face whenever an event of note occurs. We see his brother's loss of faith through his eyes, and it is he who imbues the moment with the sadness that Mel Gibson's character will not let himself feel. For his part, Gibson also gave an extremely tender performance that highlights the nuances of guiding children through a world you feel lost in yourself. Years later, cinephiles still hail that performance as one of the actor's most unique.

Shyamalan will make you see things from a different angle -- literally

Shyamalan stories entrance the audience with unique cinematography. He often relies on indirect camera angles depicting scenes through visual obstacles or reflected off other objects, like doorknobs and picture frames. In Unbreakable, during the conversation David Dunn has with the married woman on the train, the camera pans back and forth between the two of them, only ever able to see one participant as it peeks through a crack in the seats. This mirrors the perspective of the observant child who judges Dunn for taking off his ring to flirt with the woman. The angle and frame convey guilt before Dunn himself even feels it.

The doorknob reflections in The Sixth Sense are an iconic example of Shyamalan's style, and even provide us with a hint to the film's shocking conclusion: We can see Cole's reflection, but not Malcolm's, who is actually dead. In Unbreakable, Shyamalan uses his reflection technique to provide a similarly subtle bit of foreshadowing. When Elijah Price, who is revealed at the end of the film to be a criminal mastermind, states that a villain often has a slightly enlarged head, his own head appears exaggerated in the reflection of a frame beside him.

The music carries Shyamalan's stories

Music enlivens Shyamalan's movies as though it was made for them. That's because the music was made specifically for almost every Shyamalan project by James Newton Howard. Howard's work is only missing from the director's more recent films, including The Visit, and Unbreakable sequels Split and Glass. Still, the composer for the latter two of these films, West Dylan Thordson, incorporated some of Howard's themes into his soundtrack.

Despite his recent absences, Shyamalan was the first name out of Howard's mouth when Vulture asked him about his best working relationships with directors in 2020. It's clear that the two artists get each other: The scores for Shyamalan's films are deep and haunting, with cues that pierce our hearts distinctly and subtly nudge our suspicions in the right (or calculatedly wrong) directions. Howard's style is so indispensable to Shyamalan's work that his character theme for Mr. Glass, among other elements of his score, persists even into films he himself did not work on.